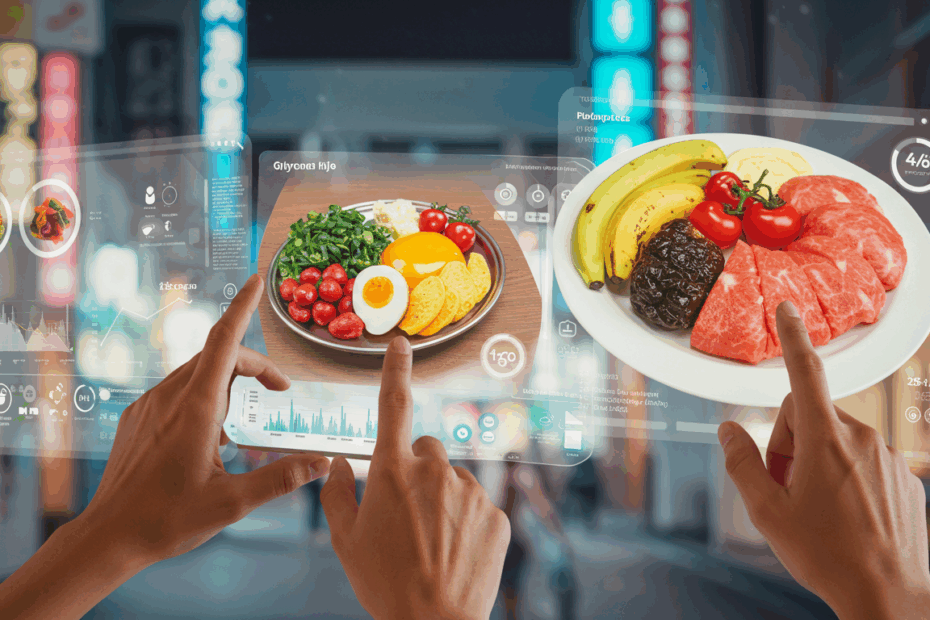

John: Alright, Lila, let’s dive into our topic for today. We’re tackling a term that sounds incredibly scientific but is, at its heart, a fundamental lifestyle concept: “Glycemic control, intake.” It’s about how the food we eat—our intake—directly influences our body’s blood sugar levels. For many, this is the key to unlocking consistent energy, better mood, and long-term health.

Lila: I’m glad you framed it like that, John. “Glycemic control” sounds like something you’d only discuss with a doctor or an endocrinologist. It can be intimidating. But framing it as a lifestyle choice makes it feel much more approachable. Where do we even begin to unpack this for our readers who might be hearing it for the first time?

John: An excellent starting point. We begin with the basics: blood sugar, or more formally, blood glucose. Every time we eat, particularly foods containing carbohydrates, our body breaks them down into glucose, which then enters our bloodstream. This glucose is our primary source of energy. “Glycemic control” is simply the process of keeping these blood glucose levels within a healthy, stable range—not too high, not too low.

Lila: Okay, so it’s not about eliminating sugar, but managing it. When people hear “blood sugar,” they often think of that sudden burst of energy after a candy bar, followed by the inevitable crash. Is that what we’re trying to avoid?

John: Precisely. Those sharp spikes and crashes are what we want to smooth out. Think of it like driving a car. You want smooth acceleration and braking, not lurching forward and slamming on the brakes. That constant lurching is tough on the engine—and in this case, the ‘engine’ is our metabolism, our pancreas, and our entire hormonal system. The goal is a steady, gentle cruise.

Lila: That’s a great analogy. So, how does our “intake” play into this? Is it just about avoiding sugary sodas and desserts?

John: That’s certainly part of it, and a significant one at that. The American Diabetes Association, for example, strongly recommends limiting added sugars and sugar-sweetened beverages. But it’s far more nuanced. It involves the *type* of carbohydrates we eat, the *combination* of foods in a meal, and even the *timing* of our meals. This is where the lifestyle aspect really comes into focus.

Lila: So, it’s not a simple “good food, bad food” list. It’s more of a strategic approach to eating. I think that’s an important distinction. People get tired of restrictive diets, but a “strategy” sounds empowering. What’s the first concept our readers need to understand to build their strategy?

John: The first concept is the Glycemic Index, or GI. It’s a rating system for foods containing carbohydrates, showing how quickly each food affects your blood sugar level when that food is eaten on its own. It’s a scale from 0 to 100, with pure glucose sitting at 100.

Lila: So high-GI foods are the ones that cause that fast, lurching acceleration you mentioned?

John: Exactly. Foods with a high GI (typically 70 or more) are digested and absorbed rapidly, leading to a quick spike in blood glucose. Think of white bread, sugary cereals, and potatoes. Low-GI foods (55 or less) are digested more slowly, causing a gentler, more gradual rise in blood sugar. These include foods like whole grains, legumes, and most fruits and vegetables.

Lila: That makes sense. But I’ve heard that GI isn’t the whole story. What if you only eat a tiny amount of a high-GI food? Does that have the same impact as a large portion?

John: You’re spot on, and that brings us to the next crucial concept: Glycemic Load, or GL. Glycemic Load takes the Glycemic Index one step further by factoring in the amount of carbohydrate in a serving of that food. The formula is essentially (GI x Grams of Carbs) / 100. This gives a much more realistic picture of a food’s impact on your blood sugar in the context of a real-world portion size.

Lila: Can you give me an example? I think that would really help clarify the difference.

John: Of course. Watermelon is a classic example. It has a high Glycemic Index, around 72. Based on that alone, you might think you should avoid it. But watermelon is mostly water; a standard serving doesn’t contain a lot of carbohydrates. So, its Glycemic Load is actually quite low, around 4 or 5. In contrast, a serving of brown rice has a lower GI, around 50, but it’s much more carb-dense, giving it a higher GL of about 16. The GL tells you that the serving of brown rice will ultimately have a greater impact on your blood sugar than the serving of watermelon.

Lila: Wow, okay. That changes everything. It means we don’t have to fear certain healthy foods like fruits just because of their GI score. We just need to be mindful of the whole picture—the quality and the quantity. This feels much less restrictive and more about being informed.

John: That’s the core of it. It’s about being informed. This isn’t about banning foods; it’s about understanding them. Once you grasp GI and GL, you can start building meals that naturally support stable blood sugar. This is the foundation of managing your “intake” for effective “glycemic control.” This is why a major goal in managing conditions like glucose intolerance is specifically focused on glycemic control—it’s that fundamental.

Lila: We’ve established the “what” and the “how” in a technical sense, John. But let’s talk about the “why.” Why should the average person, who may not have a diagnosed condition like diabetes, care so deeply about glycemic control?

John: That’s the most important question. The benefits extend far beyond managing a medical condition. The primary, day-to-day benefit is stable energy. By avoiding those sharp glucose spikes and subsequent crashes, you eliminate the infamous “afternoon slump.” Your energy levels remain more consistent, allowing for better focus and productivity throughout the day.

Lila: I can definitely relate to that 3 p.m. feeling of wanting a nap or a coffee. So you’re saying that a lunch high in refined carbs—like a big bowl of white pasta or a sandwich on white bread—is likely the culprit?

John: It’s a prime suspect. Your body gets a huge, rapid influx of glucose, and your pancreas works overtime to release insulin to manage it. The insulin does its job so effectively that it can overshoot, causing your blood sugar to drop quickly, leading to that feeling of fatigue, irritability, and brain fog. It’s a physiological rollercoaster. A balanced meal with lean protein, healthy fats, and high-fiber carbohydrates prevents this.

Lila: Beyond energy, what are the other benefits? I imagine this has an impact on mood as well.

John: Absolutely. The same hormonal fluctuations that tank your energy can also wreak havoc on your mood. That feeling of being “hangry” is a very real response to low blood sugar. By keeping levels stable, you’re promoting a more stable mood. Long-term, the benefits are even more significant. Consistently poor glycemic control is a major risk factor for developing insulin resistance and, eventually, type 2 diabetes.

Lila: So, adopting this lifestyle is a powerful preventative measure?

John: A profoundly powerful one. Think of it as investing in your future metabolic health. Research consistently shows the connection between dietary habits and glycemic control. One study published in *Cureus* in 2024 specifically found that high sugar consumption, inadequate fiber intake, and infrequent meals were significantly associated with poor glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes. While that study focused on a specific group, the principles are universal. These habits strain the system over time for everyone.

Lila: That’s a stark warning. It’s not just about feeling a bit tired; it’s about cumulative damage. What about weight management? Does that factor in?

John: It’s deeply connected. When insulin levels are constantly high due to frequent blood sugar spikes, it signals your body to store fat. It essentially puts your body in “storage mode.” By managing your glycemic response, you help keep insulin levels in a healthier range, which can make it easier to maintain a healthy weight. In fact, many successful weight management strategies, like various forms of energy restriction, are effective precisely because they help manage and improve blood glucose levels, as shown in recent studies.

Lila: So it all comes full circle. The way you eat affects your blood sugar, which affects your hormones like insulin, which in turn affects your energy, mood, and even your body’s tendency to store fat. It’s a single, interconnected system.

John: You’ve got it. It’s an elegant system when it’s in balance. And the “intake” side of the equation is our most direct and powerful tool for maintaining that balance. It’s why we need to move beyond just counting calories and start thinking about the quality and composition of what we’re eating. The science of glycemic control is really the science of how food communicates with our bodies.

Lila: Okay, John, I’m convinced of the ‘why’. Let’s get into the practical application. If a reader wants to start improving their glycemic control today, what are the most impactful changes they can make to their “intake”? Where do they start?

John: The best place to start is by re-evaluating carbohydrates. This is often the area with the biggest and most immediate impact. The key is focusing on both quantity and quality. Many approaches have proven effective, from general awareness to more structured plans. For instance, some strategies focus on controlling or restricting overall carbohydrate intake, which has long been a cornerstone for managing blood glucose.

Lila: When you say “restricting carbohydrate intake,” that sounds like a low-carb diet. Is that the only way?

John: It’s an effective way for many, but not the only one. The core principle is reducing the overall glycemic load of your diet. You can do this by lowering the total amount of carbs, or by being highly selective about the *type* of carbs you consume. The emphasis should be on choosing complex carbohydrates over simple sugars and refined grains. Instead of white rice, choose quinoa or brown rice. Instead of white bread, opt for stone-ground whole-wheat or sourdough bread.

Lila: What makes those “complex” carbs better for glycemic control?

John: It comes down to their structure. Complex carbohydrates are made of long, complex chains of sugar molecules. They also come packaged with fiber. This structure means your body has to work harder and longer to break them down, leading to that slow, steady release of glucose we’re aiming for. Simple carbs, like those in refined sugar or white flour, are already broken down into short chains, so they hit the bloodstream almost instantly.

Lila: So, it’s not “no carbs,” it’s “slow carbs.” I like that. What about fiber? You’ve mentioned it a few times. It seems to be a real hero in this story.

John: It absolutely is. High-fiber diets are a critical component. A 2024 study in *Cureus* directly linked inadequate fiber intake with poor glycemic control. There are two types of fiber, but soluble fiber is particularly beneficial here. It dissolves in water to form a gel-like substance in your digestive tract. This gel slows everything down—it slows the digestion of carbohydrates and the absorption of glucose. This blunts the blood sugar response significantly.

Lila: Where do we find this amazing soluble fiber?

John: It’s abundant in foods like oats, barley, apples, citrus fruits, carrots, beans, and peas. Simply starting your day with a bowl of oatmeal instead of a sugary cereal, or adding a side of black beans to your lunch, can make a noticeable difference. It’s a simple swap with a profound metabolic benefit. This is why a key recommendation for natural blood sugar management is to incorporate more soluble fiber into your meals.

Lila: That’s very actionable. Now, what about the other parts of the meal? We can’t live on fiber and slow carbs alone. What role do protein and fats play?

John: They play a crucial supporting role. Like fiber, protein and healthy fats also slow down digestion. When you include a source of lean protein—like chicken, fish, or tofu—and a source of healthy fat—like avocado, nuts, or olive oil—in a meal, you lower the overall glycemic load of that meal. They act as a brake on carbohydrate absorption.

Lila: So, a balanced plate is key. It’s not just about what you’re eating, but what you’re eating it *with*. This is why snacks recommended for people with type 2 diabetes often pair a carb with a protein or fat, right? Like an apple with peanut butter?

John: That’s the perfect example. The apple provides carbs and fiber, while the peanut butter provides protein and fat. Together, they make for a snack that provides sustained energy without a dramatic blood sugar spike. Health authorities often suggest snacks that include protein, fiber, and fat, such as Greek yogurt or a handful of nuts, for this very reason. It’s about building a buffer into your meals and snacks.

Lila: This leads to another interesting idea I saw in the research: meal composition, or food order. I read a fascinating tip that suggests eating your carbohydrates last. Is there science to back that up?

John: There is, and it’s a simple but effective bio-hack. Studies have shown that eating the fiber, protein, and fat components of your meal first—for instance, eating your salad and chicken before you eat your bread or potatoes—can significantly lower the post-meal glucose spike. The fiber, fat, and protein essentially line your digestive system, preparing it to handle the carbohydrates more slowly when they do arrive.

Lila: That is so cool! It’s the same food, just eaten in a different order, and it has a different metabolic effect. It doesn’t cost anything or require special ingredients. What about meal timing in general? The *Cureus* study mentioned “infrequent meals” as a problem.

John: Yes, consistency is important. When you skip meals, you’re more likely to experience a significant drop in blood sugar, which can lead to intense hunger and overeating later on—often reaching for high-GI, quick-energy foods. This creates that vicious spike-and-crash cycle. On the other hand, some people find success with structured eating patterns like intermittent fasting or time-restricted eating, where they consume all their calories within a specific window, say 8 hours. Recent research has shown these strategies can be effective for weight loss and glycemic control, likely because they can improve insulin sensitivity and give the digestive system a long rest.

Lila: So it’s not contradictory? Regular meals for some, time-restricted eating for others?

John: It highlights a critical point: personalization. There isn’t one single “perfect” plan. For some, three balanced meals a day prevent hunger and overeating. For others, a compressed eating window works better. The common thread is moving away from erratic, unstructured grazing, especially on highly processed foods. A clear plan is essential for managing glycemia. The key is finding a consistent, sustainable pattern that works for your body and lifestyle.

John: We’ve covered the “intake” part of the equation in great detail, Lila. But true glycemic control is a lifestyle, which means it extends beyond the plate. There are other powerful levers we can pull to support our metabolic health.

Lila: I’m guessing exercise is at the top of that list. We all know it’s good for us, but how does it specifically impact blood sugar?

John: It has a direct and immediate effect. When you exercise, your muscles need energy. They can pull glucose directly from your bloodstream to fuel their work, which naturally helps lower blood sugar levels. Regular physical activity also makes your body’s cells more sensitive to insulin, meaning your pancreas doesn’t have to work as hard to do its job. It’s a two-fold benefit.

Lila: Does it have to be an intense, hour-long gym session to count?

John: Not at all. And this is perhaps one of the most exciting and empowering findings in recent research. A 2025 study published in the journal *Nature* found that even a brief, 10-minute walk taken immediately after a meal can be a highly effective and feasible approach for managing hyperglycemia, or high blood sugar. The timing is key. Moving your body right after eating helps your muscles soak up some of the glucose from that meal before it has a chance to spike in your bloodstream.

Lila: A ten-minute walk! That’s it? That is incredibly accessible. Most people can fit that in after lunch or dinner. It reframes exercise from a chore you have to schedule to a simple, integrated part of your meal routine, like brushing your teeth.

John: That’s the perfect way to look at it. It’s about creating small, sustainable habits that stack up to create a significant impact. It’s not about perfection; it’s about consistency. A short walk, taking the stairs, doing some squats while you wait for the kettle to boil—it all contributes to better glycemic management.

Lila: We’ve talked about diet and exercise. What else is in the lifestyle toolkit for glycemic control?

John: Stress and sleep are the other two pillars. Chronic stress elevates cortisol, a hormone that can make your cells more resistant to insulin and signal your liver to release more glucose into the bloodstream. And a lack of quality sleep has a similar effect, disrupting appetite-regulating hormones and impairing insulin sensitivity the very next day. Managing stress and prioritizing sleep are non-negotiable for long-term glycemic health.

Lila: It’s amazing how interconnected everything is. It’s not just about food. It’s about how we eat, how we move, how we sleep, and how we handle stress. Looking ahead, what does the future of glycemic control look like? It seems like we’re moving towards a much more personalized approach.

John: We absolutely are. The future is all about personalization, powered by technology. We’re seeing the rise of continuous glucose monitors (CGMs), which are no longer just for people with diabetes. They allow anyone to see in real-time how their body responds to specific foods, exercise, and stress. This bio-feedback is incredibly powerful.

Lila: So instead of relying on a generic GI chart, I could see exactly how *my* body reacts to a specific bowl of oatmeal versus my friend’s reaction to the same meal?

John: Precisely. We are all unique. Research from 2025 in *Nature Scientific Reports* is already focusing on predicting an individual’s postprandial glucose excursions—that’s the rise in blood sugar after a meal. The goal is to enable personalized dietary prompts for glycemic control. Imagine an app that knows your unique metabolic response and can suggest, “For you, it’s better to have the apple with almond butter, not peanut butter,” or “A 15-minute walk after this particular meal would be optimal.”

Lila: That’s incredible. It takes the guesswork out of the equation. It’s a shift from general guidelines to specific, data-driven personal advice.

John: It is. We are also seeing deeper research into the gut microbiota. A 2024 study investigated how our unique gut bacteria composition can be used to predict blood sugar control. The future may involve analyzing your gut microbiome to create a completely customized nutrition plan. The overarching trend is clear: we’re moving away from one-size-fits-all diets and towards a holistic, personalized, and proactive approach to managing our metabolic health. It’s an exciting time.

Lila: So, to wrap this all up for our readers, what’s the final takeaway? If they remember just one thing from this entire discussion, what should it be?

John: The final takeaway is that you have more control than you think. Glycemic control isn’t a restrictive punishment; it’s an empowering lifestyle based on understanding the conversation between your food and your body. Start small. You don’t have to overhaul your entire life overnight. Pick one thing. Maybe this week, you focus on adding more fiber to your lunch. Or maybe you commit to that 10-minute walk after dinner.

Lila: I love that. It’s about making one better choice at a time. Swap white bread for whole grain. Add a source of protein to your breakfast. Eat your salad first. These aren’t drastic changes, but based on everything we’ve discussed, their cumulative effect over time could be life-changing.

John: Exactly. It’s about progress, not perfection. By focusing on your intake—the quality of your carbs, the presence of fiber, protein, and fats—and supporting it with simple lifestyle habits like a post-meal walk, you are actively investing in your present and future well-being. You’re smoothing out that ride, ensuring your body has the steady, reliable energy it needs to thrive. And that is the true essence of living a lifestyle of glycemic control.